The story starts in 2021, when countries from all over the world got together under the OECD's Inclusive Framework to solve an issue that had been there for a long time: multinational firms shifting profits to locations with low or no taxes.

During the Biden administration, Janet Yellen, who used to be the Secretary of the Treasury, had a key role in making this happen. More than 140 countries signed up, and by the end of 2025, many of them were already utilizing it.

“This agreement represents a historic victory in preserving U.S. sovereignty and protecting American workers and businesses from extraterritorial overreach.

The Trump administration comes back in 2025. From the very beginning, President Trump made it plain that the OECD accord would have "no force or effect" in the US. On Day One, he signed an executive order to that effect.

The 2021 Agreement and the Push for a Global Minimum Tax

Consider how Apple, Google, and Nike make a lot of money in areas like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and Ireland, where they don't do much business. Businesses can pay very little tax on profits that are genuinely produced in other areas when they are in these "tax havens."

The 2021 agreement, which is part of a larger BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) campaign, set a minimum effective corporate tax rate of 15% for large multinationals that make more than a particular amount of money (approximately €750 million).

If a corporation paid less than 15% in one nation, other countries could apply "top-up" taxes to make up the difference. The premise was simple: stop the "race to the bottom," which is when governments decrease taxes to get enterprises to move there. This hurts government revenue everywhere.

She thought it would make things more equitable, stop businesses from not paying their taxes, and make sure that the biggest businesses paid what they owed. People felt it was a significant step toward getting everyone to work together on taxes.

By the end of 2025, implementation was well underway in many jurisdictions, with rules designed to ensure multinationals paid at least 15% effective tax worldwide.

More Read

U.S. Pushback Under the Trump Administration

Republicans in Congress have been against it. They believe it would make it tougher for American businesses to compete, raise expenses for U.S. enterprises, and let foreign governments decide how U.S. companies should be taxed.

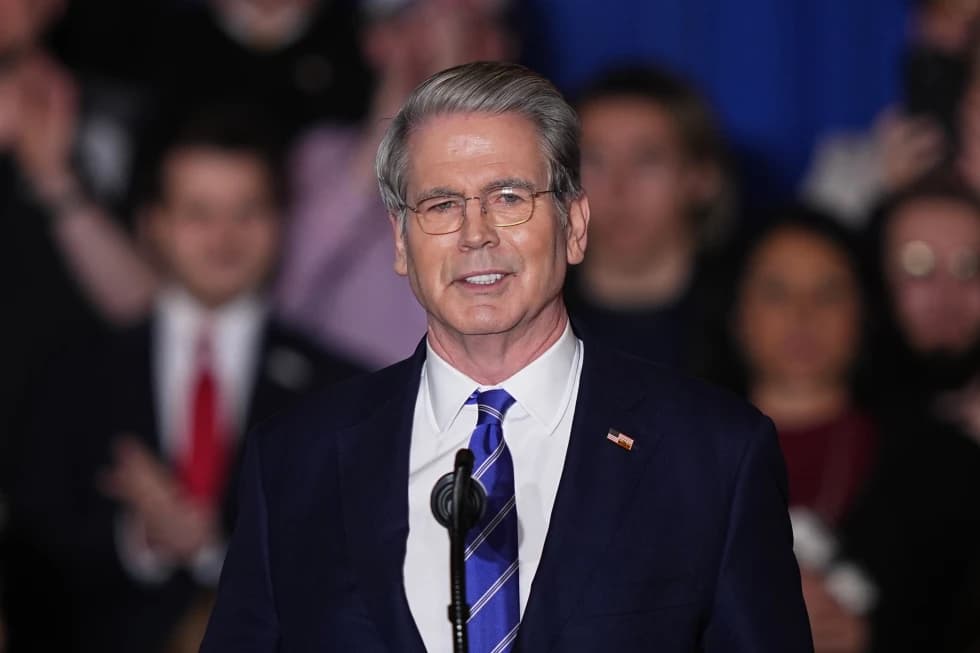

The talks got more serious. Scott Bessent, the new Treasury Secretary, was in charge of the Trump team's cooperation with friends in the Group of Seven (G7) and the bigger OECD framework.

A contract was reached in June that will extend until the middle of 2025. It led to the announcement of a "side-by-side" accord in January 2026. This deal had extended safe harbors and carve-outs.

The new deal primarily lets corporations in the U.S. off the hook for the Pillar Two obligations. They are still exclusively subject to U.S. tax laws, notably the GILTI requirements from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which set a global minimum tax rate.

Foreign governments can't actually charge U.S. companies' subsidiaries more taxes to make up for the fact that profits are taxed less in other locations.

Reactions to the Side-by-Side Agreement

Secretary Bessent called it a "historic victory in protecting U.S. sovereignty and keeping American workers and businesses safe from overreach from outside the U.S." He underlined that the treaty safeguards America's freedom to tax its own firms without intervention from other countries.

Mathias Cormann, the Secretary-General of the OECD, likewise had a good attitude. He said the ruling was a "landmark decision in international tax cooperation" that "makes taxes more certain, less complicated, and protects tax bases." He thanked the over 150 countries that worked together.

This is a significant gain for American companies and the people who work for them. Big American businesses can keep doing business and have more freedom to make money all around the world.

Republican Senators Mike Crapo and Jason Smith, who are also the heads of the House Ways and Means Committee, stated that this was another step in a "America First" approach that reversed what they called the "unilateral global tax surrender" that happened when Biden was president.

Tax transparency groups and individuals who don't like it, on the other hand, think this is a significant step back. The FACT Coalition and the Tax Justice Network claim that this sets back almost ten years of work.

Criticism from Tax Justice Advocates

Secretary Bessent called it a "historic victory in protecting U.S. sovereignty and keeping American workers and businesses safe from overreach from outside the U.S." He underlined that the treaty safeguards America's freedom to tax its own firms without intervention from other countries.

Mathias Cormann, the Secretary-General of the OECD, likewise had a good attitude. He said the ruling was a "landmark decision in international tax cooperation" that "makes taxes more certain, less complicated, and protects tax bases." He thanked the over 150 countries that worked together.

This is a significant gain for American companies and the people who work for them. Big American businesses can keep doing business and have more freedom to make money all around the world.

Republican Senators Mike Crapo and Jason Smith, who are also the heads of the House Ways and Means Committee, stated that this was another step in a "America First" approach that reversed what they called the "unilateral global tax surrender" that happened when Biden was president.

Tax transparency groups and individuals who don't like it, on the other hand, think this is a significant step back. The FACT Coalition and the Tax Justice Network claim that this sets back almost ten years of work.

Broader Implications and Ongoing Discussions

The conversations concerning taxation around the world are still going on. Pillar One is about changing who can tax major tech and digital services, while Pillar Two is about the lowest tax rate.

Pillar Two is the main focus of the U.S. exception, but Bessent says that conversations about digital taxes are still going on and that there is still "constructive dialogue."

The pact gives businesses a little bit of peace of mind about taxes that will be owed in 2026 and after. Without it, American companies could have had to contend with uncertainty or revenge from other countries.

But it does illustrate that globalization is still producing problems. Even the most ambitious international treaties can be changed by national interests, especially those of large economies.

This new OECD agreement is a good middle ground in a world that is split. It preserves U.S. interests while still letting everyone else work toward the broader picture. There is still a lot of controversy regarding whether it genuinely eliminates profit shifting or just moves the problem to a different place.

Benjamin Hayes

Business Journalist

Benjamin Hayes is a seasoned business journalist with a special focus on corporate finance, global markets, and entrepreneurial trends. He has covered major startups, tech investments, and economic shifts in multiple sectors.

No next post